Also read: The Gastrointestinal Tract

Reference

This discussion is based on Dr. Edgar M. Rotairo’s presentation.

Anatomy and Physiology

The alimentary tract is the main route of nutrition for the human body, and starts from the mouth, through the esophagus, into the stomach, through the small and large intestines, then in the rectum and out the anus. Along with the alimentary canal, additional accessory organs of digestion aid in the digestion of ingested substances.

Liver

The largest gland (internal organ) in the body, located on the right side of the body under the diaphragm. It consists of four lobes (divided into right and left lobes by the falciform ligament) suspended from the diaphragm and abdominal wall by the falciform ligament.

Functions of the Liver

Link to original

- Storage: of copper, iron, magnesium, Vitamins B2, B6, B9, B12, and fat-soluble vitamins (ADEK).

- Protection: phagocytic and pinocytic Kupffer cells detoxify xenobiotics and foreign bodies, also aiding in the breakdown of erythrocytes.

- Metabolism: aids in breaking down amino acids forming urea, synthesis of plasma proteins, and the metabolism of carbohydrates and fats.

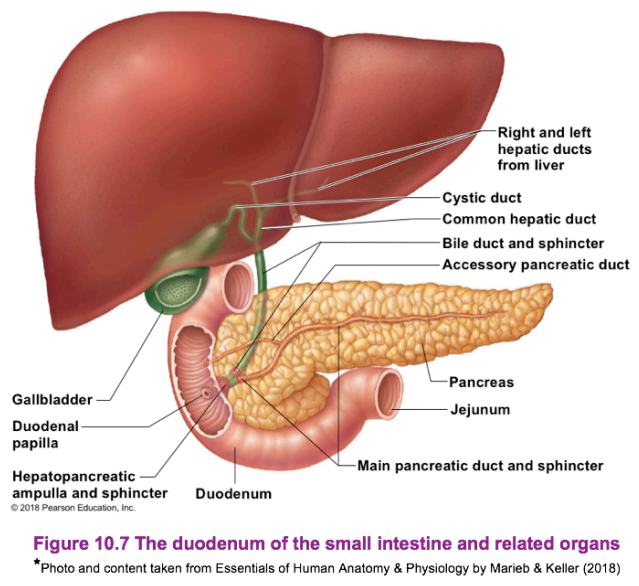

- In the digestive context, its function is to produce bile. Bile leaves the liver through the hepatic duct and enters the duodenum through the bile duct. Bile is a yellow-green, watery solution containing bile salts, pigments (mostly bilirubin), cholesterol, phospholipids, and electrolytes. Bile is used to emulsify fats.

Gallbladder

The gallbladder is a green sac found in a shallow fossa in the inferior surface of the liver. It serves as storage for bile if no digestion is occurring, with bile backing up the cystic duct. When in the gallbladder, bile loses its water content, and becomes more concentrated. Once fats enter the duodenum again, it is released for digestion. It is divided into the neck, body, and fundus.

Link to original

Pancreas

A soft, pink, and triangular (fish-shaped) gland found posterior to the parietal peritoneum (mostly retroperitoneal), behind the stomach. It extends from the spleen to the duodenum. It is segmented into the head, body, and tail of the pancreas. This produces a wide spectrum of digestive enzymes that break down all categories of food. These enzymes are sent into the duodenum. Alkaline fluids introduced with enzymes neutralizes the acidic chyme from the stomach. The pancreas have areas known as islets of langerhans which have cells (alpha, beta, delta, C) that also produce hormones:

- Insulin: used for moving glucose into cells (transcellular glucose transportation) and inhibits digestion of fats and proteins, consequently reducing blood glucose levels; produced by beta cells.

- Glucagon: counteracts the action of insulin by increasing hepatic glucose production (gluconeogenesis); produced by alpha cells.

Function

Link to original

- Exocrine: 80% of the organ is composed of acinar cells that secretes enzymes.

- Endocrine: 20% of the organ is composed of islets of langerhans that secrete hormones (insulin, glucagon).

Bleeding Disorders

Gastrointestinal bleeding, also known as gastrointestinal hemorrhage, involves any form of bleeding along any part of the gastrointestinal tract whether in the mouth or in the rectum. Depending on its location, it may be classified as an upper GI bleed or a lower GI bleed.

Upper GI Bleed

| Common Causes | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Peptic Ulcer Disease | 20% – 50% |

| Gastroduodenal Erosion | 8% – 15% |

| Esophagitis | 5% – 15% |

| Varices | 5% – 20% |

| Mallory-Weiss Tearing | 8% – 15% |

| Vascular Malformation | 5% |

In upper GI bleeding, the following symptoms appear:

- Melena or Melenic stools; stool that are black (dark-colored), tarry, and foul-smelling.

- Hematemesis, either red (fresh blood) or coffee-ground (blood altered by stomach acids and enzymes).

- Dyspepsia

- Heartburn (Pyrosis) or Epigastric pain

- Abdominal Pain

- Dysphagia, a difficulty in swallowing

- Jaundice if the liver is implicated

- Weight loss from malabsorption or secondary to loss of appetite

- Syncope or presyncope due to decreased perfusion or decreased blood volume/pressure

- Pallor

Lower GI Bleed

| Common Causes | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Diverticulosis | 20% – 65% |

| Angioectasia | 40% – 50% |

| Ischemic Colitis | - |

| Hemorrhoids | 2% – 5% |

| Colorectal Neoplasia | - |

| Postpolypectomy Bleeding | 2% – 8% |

| Solitary Rectal Ulcer | - |

| Radiation Proctopathy | - |

- Diverticulosis and angioectasia account for 80% of adults with LGIB.

- Infectious colitis and inflammatory bowel disease are the common causes in children.

- Meckel’s diverticulum and intussusception are the most common causes of massive LGIB in children younger than 2 years old.

In lower GI bleeding, the following symptoms appear:

- Hematochezia: fresh blood in stool such as in hemorrhoids or anal fissure.

- Bloody Diarrhea: typical of colitis.

- Febrile episodes potentially related to colitis, diverticulitis, or potential infections.

- Hypovolemic Shock or Dehydration from severe blood loss.

- Abdominal cramps or pain due to related inflammation, obstruction, or other underlying causes of LGIB.

- Hypotension also from severe blood loss.

- Decreased hemoglobin levels from direct losses in bleeding.

- Pallor from reduced blood volume and subsequent decreased perfusion.

Diagnostic Examination

- Determine the history of bleeding:

- Duration and quantity

- Associated symptoms

- Previous history of bleeding

- Current medications such as anticoagulants and some antibiotics that can contribute to bleeding risks

- Alcohol use

- NSAID or ASA (aspirin) use, as these medications can result in gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Allergies

- Associated medical illnesses such as liver disease, coagulopathies, inflammatory bowel diseases, etc.

- Previous surgery as potential causes for GI bleeding

False Positives

- Diet: the ingestion of certain fruits (cantaloupe, grapefruit, figs), uncooked vegetables (radish, cauliflower, broccoli), and red meat may produce a blood-like appearance upon emesis or defecation.

- Preparations: the use of methylene blue, chlorophyll, iodide, cupric sulfate, and bromide preparations can also produce the same effect.

Hematochezia

Hematochezia (bright red, maroon) often signifies lower GI bleeding, or a rapid transit time of an upper GI bleed (10% to 15% of patients). A more proximal source of significant bleeding must be excluded before assuming the bleeding is from the GI tract.

- Physical Examination:

- Vital signs and postural changes in heart rate and blood pressure are insensitive and nonspecific. This includes tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypotension related to bleeding.

- Skin signs may appear in shock (color, warmth, moisture) or vascular/hypocoagulable diseases (lesions; telangiectasia, bruises, petechiae)

- Rectal Examination: rectal and stool examinations are often key to making or confirming the diagnosis of GI bleeding. Recognition and management of patients with GI bleeding can start with the finding of red, black, or melenic stool.

- Fecal Occult Blood Testing: testing for the presence of hemoglobin in occult amounts in stool confirmed by tests such as Hemoccult or HemaPrompt. In patients with a single, major episode of UGIB, FOBT returns positive in 14 days.

- Hematocrit: changes in Hct may lag significantly behind actual blood loss. The initial hematocrit may be misleading in patients with preexisting anemia or polycythemia. Additionally, patients without bleeding may exhibit low Hct after a rapid infusion of crystalloid (hemodilution).

- Hemoglobin: a concentration of 8 g/dL or less from acute blood loss often require blood therapy (+3% Hct, +1 mg/dL Hgb per unit of blood)

- Coagulation Profile: PT (prothrombin time) may be elevated, indicating the presence of Vit. K deficiency, liver dysfunction, warfarin therapy, or consumptive coagulopathy.

- Serial platelet counts are used to determine the need for platelet transfusions (>50,000/mm³)

- ABG and Electrolyte Balance: patients with repeated vomiting may develop hypokalemia, hyponatremia, and metabolic alkalosis.

- CT Angiography is the gold standard for the diagnosis of GI bleeding.

- Endoscopy: the use of an endoscope to physically visualize the gastrointestinal tract. This may be done in the form of an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (ED; upper GI) or colonoscopy (lower GI).

Treatment and Management

- Quick Identification is important in preventing complications and implementing early interventions.

- Aggressive Resuscitation may be necessary in severe bleeding to reestablish stable vitals and blood parameters.

- Establish good access: two large-bore (gauge 18) peripheral IVs or a triple-lumen or Cordis catheter if in MICU.

- Replace intravascular volume for patients who are hypotensive and/or orthostatic. (a) Normal saline is given as bolus, (b) PRBCs are given for anemic patients, and (c) FFP/Platelets are given for massive GI bleeds.

- Nasogastric Intubation and NG Lavage: placement and confirmation of placement; flushing the stomach— inject 250 cc NS, then draw 250 cc back, then repeated up to a total of 2L or until fluid withdrawn are clear. This is done to flush out any clots or other contents of the stomach. However, this is contraindicated in patients with facial trauma, nasal bone fracture, those with esophageal abnormalities (e.g. strictures, diverticuli), and those who have ingested caustic substances or experienced esophageal burns.

- Prompt Consultation

- Pharmacology:

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (8 mg/hr with 80 mg loading dose): acidity dissolves blood clots, which can increase bleeding. PPIs reduce gastric acid secretion, promoting the healing of ulcers and erosions as well as stabilizing thrombi.

- Somatostatin Analogues (Octreotide; 25–50mcg/hr for at least 24 hours). These also reduce gastric secretions, and are used in patients with esophageal varices and acute upper GI bleeding. This may be supplemental to endoscopic sclerotherapy (varicose veins are chemically sealed shut).

Treatment Regime for H. Pylori

Regimen Side Effect Rating Cure Rate Clarithromycin + Metronidazole + PPI Medium 80–90% Amoxicillin + Clarithromycin + PPI Medium-Low 80–90% Amoxicillin + Metronidazole + PPI Medium 80–90% Helidac + H₂ Blocker Medium-High 80–85% Prevpak Medium-Low 81–92%

- Surgical Treatment is dependent on the nature of the cause of bleeding. A particular distinction for methodology is whether or not the bleed is variceal in nature. For non-variceal bleeding, surgery is reserved for patients with failed medical management. The treatment used depends on the cause, but is commonly performed in the context of a bleeding peptic ulcer. See the next section for variceal bleeding.

Variceal Bleeding

Variceal bleeding is suspected in liver disease or cirrhosis. It occurs from resultant portal hypertension and the development of porto-systemic anastomosis (connection of portal and systemic circulation). Pharmacologic treatment may be used to resolve bleeding before the necessity for radical approaches:

- Somatostatin/Octreotide vasoconstricts splanchnic circulation and reduces pressure in the portal system

- Terlipressin: vasoconstricts splanchnic circulation and reduces pressure in the portal system

- Propanolol as primary prevention for those with varices.

Balloon Tamponade

As a rare intervention, a Sengstaken-Blakemore Tube is temporarily used as a balloon tamponade if endoscopic management fails.

Surgery may be done if prior interventions have been ineffective:

- Band ligation physically closes bleeding varices.

- Sclerotherapy shuts off varices through the administration of chemical agents through an endoscope.

- Transjugular Intrahepatic Porto-Systemic Shunt (TIPSS) is the placement of a shunt between the hepatic and portal vein to alleviate portal pressure. However, this can worsen hepatic encephalopathy, and is only performed if medical and endoscopic management have been ineffective.

- Surgical porto-systemic shunts (often spleno-renal) alleviates porto-systemic pressure.

Radiation may be used to selectively catheterize and embolize vessels feeding the varices, if medical and endoscopic attempts at management have been unsuccessful.

Traumatic Disorders

Injuries induced by physical damage to the abdomen. These include incidents such as blunt trauma and penetrating injuries. The abdominal cavity contains many organs, including solid organs (liver, spleen, kidney, pancreas, etc.) and hollow organs (GI tract, bladder, appendix, gall bladder, etc.)

| Injury/Finding | Suspected Damage |

|---|---|

| Blunt Abdominal Trauma | Spleen: most commonly injured organ |

| Referred Left Shoulder Pain | Splenic Rupture |

| Lower Left Rib Fractures | Splenic Injury |

| Blunt and Penetrating Injuries | Liver |

| Grey-Turner’s Sign (bluish discoloration of lower flank/back) | Retroperitoneal bleeding of pancreas, kidney, or pelvis (fracture) |

| Cullen Sign (bluish periumbilical discoloration) | Peritoneal bleeding, common in pancreatic hemorrhage |

| Kehr Sign (shoulder pain when supine) | Diaphragmatic irritation from splenic injury, free air, or intra-abdominal bleeding |

| Balance Sign (dull percussion in LUQ) | Sign of splenic injury; blood accumulating in subcapsular or extracapsular spleen |

| Labial and Scrotal Sign | Pooling of blood in the scrotum or labia |

| London/Seatbelt Sign | - |

Mechanisms of Injury

- Crushing: direct application of blunt force to the abdomen

- Shearing: sudden deceleration applying shearing force on attached organ

- Bursting: raised intraluminal pressure due to compression in hollow organs, resulting in rupture

- Penetration: the disruption of bony areas by blunt trauma may generate bony spicules that can cause secondary penetrating injuries.

Signs and Symptoms

General findings of abdominal trauma involve mechanisms involved in blood loss:

- Increased pulse pressure: loss of total blood volume (≤15%) increases pulse pressure

- Rising HR and RR as blood loss continues

- Hypotension after significant blood loss (30%+ loss)

- Abdominal pain, fever, nausea and vomiting may take hours to become clinically apparent.

| Injury | Nature of S/S |

|---|---|

| Pancreatic Injuries | Subtle signs and symptoms, making diagnosis elusive |

| Duodenal Injuries | Clinical signs are slow to develop, commonly occurring after a high-speed vertical or horizontal decelerating trauma. |

| Duodenal Rupture | Usually contained within the peritoneum |

| Pancreatic Injury | Rapid deceleration or a severe crush injury, such as unrestrained drivers crashing into a steering wheel or a cyclist falling against their handlebar. |

Remember— Pears and Pitfalls of Abdominal Trauma

- Abdominal trauma may present with deceptively unimpressive physical exams; injuries are covert. As such, the details of the mechanism of injury should be elicited in order to provide appropriate management.

- Gunshot penetrating trauma has a much higher morbidity and mortality compared to a stab wound.

- Bedside sonography is increasingly useful for diagnosing hemoperitoneum in blunt abdominal trauma.

- The finding of free fluid in Morrison’s pouch is pathognomonic for hemoperitoneum.

Assessment

As mentioned, it is important to determine the details of the trauma experienced by the client. These guide care and management especially in the absence of clearer indicators:

- Motor Vehicle Accidents (MVAs): determine the speed of collision, the positions of each colliding car, the position of the client within the car on impact, the use of a seatbelt, and the extent of car damage.

- Falls: height fallen, landing material, body alignment on impact

- Gunshot Wounds (GSW): the type of gun used, distance from the shooter, and number of shots heard

- Stab Wounds: the type of weapon used

- The Primary Survey can be used as part of the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) Algorithm:

| Survey (ABCDE) | Content |

|---|---|

| Airway with C-Spin Protection | Is the patient speaking in full sentences? |

| Breathing and Ventilation | Is breathing labored? Are breath sounds symmetrical? Does the chest rise with respirations? - Oxygen therapy: nasal cannula, face mask |

| Circulation with Hemorrhage Control | Are pulses present and symmetric? Does the skin appear normal, warm, and well perfused? - Establish two large bore (18 gauge) antecubital IVs for resuscitation - Monitor the patient |

| Disability | What is the patient’s GCS scale? Are they able to move all of their extremities? |

| Exposure and Environmental Control | Completely expose the patient. How is the rectal tone? Is there gross bleeding through the rectum? |

- Following an intact primary survey, adjunct interventions and resuscitation may begin. Adjunct interventions include the following as necessary: EKG, ABG, CXR, Pelvis X-ray, Urinary Catheterization, E-FAST Exam, and/or DPL.

- E-FAST and/or DPL are used to determine hemoperitoneum. Bedside sonography may be used.

- The Secondary Survey includes a complete history and physical examination, done after the primary survey and once vital functions are returning to normal. An AMPLE history is taken:

- Allergies

- Medications

- Past Medical History

- Last Meal

- Events Surrounding Injury

- System-based Assessment:

- Abdomen: inspection, auscultation, percussion, palpation; find all wounds, ecchymosis, deformities, entry and exit wounds (penetrating trauma), and any evisceration.

- Perineum, Rectum, Genitalia: all are examined

- Rectum: examined for a high-riding prostate, lack of rectal tone, or heme-positive stools.

Diagnostic Examination

- Chest Radiograph: visualization of the thoracic cavity, especially useful for evaluating for herniated abdominal contents and free air under the diaphragm.

- Anteroposterior Pelvis Radiograph: identify pelvic fractures (associated with significant blood loss, intra-abdominal injury)

- Ultrasonography: a focused assessment for a focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination. This is a widely accepted primary diagnostic study done by trained doctors, surgeons, or radiologists.

- Free intraperitoneal fluid is associated with many clinically significant injuries. This is also found in hypotensive patients with blunt abdominal trauma.

- Serial FAST examinations can determine the rate of hemorrhage; this method has essentially replaced diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) for blunt abdominal trauma.

Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage

A DPL is now a second-line screening test with the use of CT and Bedside Ultrasound. It is used in blunt trauma, and can be used for:

- Patients who are severely hemodynamically unstable and are unable to leave the ED for a CT

- Patients with an equivocal physical examination, but with unexplained hypotension.

…but is absolutely contraindicated if surgical management is clearly indicated. A DPL would only delay treatment. Other conditions such as advanced hepatic dysfunction, severe coagulopathies, and previous abdominal surgeries or a gravid uterus may be considered as contraindications.

The result of a DPL is considered positive if any of the following are true:

- More than 10 mL of gross blood is aspirated immediately

- The red blood cell count if higher than 100,000/mm³

- The white blood cell count is higher than 500/mm³

- Bile is present

- Vegetable matter is present

- Computed Tomography Abdominopelvic CT with IV Contrast: a non-invasive gold standard study for the diagnosis of abdominal injury. Its major advantage over X-ray is its precision in locating and grading an injury, as well as quantifying and differentiating free intraperitoneal fluid. This is the ideal study to evaluate for retroperitoneal injuries. Contrast may be given through IV, by mouth, or rectum

| IV | Oral | Rectal |

|---|---|---|

| Contrast is injected into a vein through a small needle | Used to enhance CT images of the abdomen and pelvis | Used to enhance CT images of the larger intestines and other organs in the pelvis |

| Used to highlight blood vessels and to enhance the tissue structure of various organs such as the liver and kidneys | 1. Barium sulfate is the most common oral contrast agent used in CT 2. Gastrografin is a secondary contrast agent | For rectal CT contrast (barium and gastrografin, same as oral) but with different concentrations |

| Blood vessels and organs filled with the contrast to “enhance” and show up as white areas on the x-ray or CT images | Travels into the stomach and then into the gastrointestinal tract. These absorb CT or X-ray waves, differentiating them in the produced image | Outlining the large intestines (colon) |

Outcomes

- All patients with identifiable injuries on imaging or DPL should be admitted or transmitted to a hospital or trauma center for further inpatient monitoring and care.

- Patients with no injuries and continued abdominal pain are admitted for observation and serial abdominal exams.

- Patients with no injuries and a benign physical exam can be discharged to home with instructions for indications to return to the facility.

Management

In acute trauma, it is important to perform aggressive resuscitation, control bleeding, and ensure that patients are fully resuscitated and to reduce the incidence and severity of organ failure. Then, surgery can be used to limit further damage and repair damaged tissues. Operations are tailored to the patient’s physiology, and procedures may be staged in order to prevent physiological exhaustion.

Massive Transfusion Complications

- Hypothermia: blood products are chilled in storage. When used for rapid infusion, this may cause significant hypothermia. To counteract this complication, blood warmers are routinely used for rapid transfusions at ~50 mL/kg/hr in adults or 15 mL/kg/hr in children.

- Electrolyte Imbalance: citrate anticoagulants in stored blood can cause toxicity— citrate may bind Mg2+, causing arrhythmias, affect ionized plasma Ca2+, and K+ levels. ECG monitoring is important to determine electrolyte levels.

Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

A sustained intraabdominal pressure of greater than 20 mm Hg with or without an abdominal perfusion pressure of less than 60 mm Hg.

- Intraabdominal pressure (IAP) is a pressure within the abdominal cavity. In most critically ill (ICU) patients, an IAP of 5 to 10 mm Hg is normal. Additionally, obese and pregnant individuals may also have a higher baseline IAP (as high as 10 to 15 mm Hg) without consequence. However, in a normal health individual, IAP only ranges from 0 to 5 mm Hg.

- Abdominal perfusion pressure (APP) is calculated by subtracting IAP from MAP (), and denotes the amount of pressure required to push blood through the abdomen’s blood vessels. When IAP gets closer, APP goes down and indicates that blood vessels are being compressed by the IAP, which restricts blood flow to the abdominal viscera and organs.

- Intraabdominal hypertension (IAH) is a sustained IAP of >12 mm Hg that often causes occult ischemia, but does not produce obvious organ failure. This becomes ACS when IAP reaches >20 mm Hg and new organ dysfunction is found.

| Pressure | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 0 – 5 mm Hg | Normal |

| 5 – 10 mm Hg | ICU |

| 10 – 15 mm Hg | Obese, Pregnant |

| >12 mm Hg | IAH |

| 15 – 20 mm Hg | Dangerous IAH (Consider non-invasive interventions) |

| >20 – 25 mm Hg | Impending ACS (Consider decompressive laparotomy) |

Risk Factors

- Diminished abdominal wall compliance: trauma, respiratory failure, burns

- Increased intraluminal contents: gastroparesis, ileus, colonic pseudo-obstruction

- Increased abdominal contents: hemo-/pneumoperitoneum, ascites, liver dysfunction

- Capillary leak/fluid resuscitation

Indications for IAP Monitoring

A patient must be monitored for increasing IAP in the presence of sepsis, visceral compression/reduction, surgery (AAA repair, fluid volume excess), and trauma. Monitoring can be done through:

- Intragastric Monitoring

- Intracolonic Monitoring

- Intravesical Monitoring (via the bladder), the standard method; minimally invasive, accurate, simple.

Etiologies

- Retroperitoneal: pancreatitis, retroperitoneal, pelvic bleeding, contained AAA rupture, aortic surgery, abscess, visceral edema

- Intraperitoneal: intraperitoneal bleeding, AAA rupture, acute gastric dilatation, bowel obstruction, ileus, mesenteric venous obstruction, pneumoperitoneum, abdominal packing, abscess, visceral edema secondary to resuscitation (SIRS)

- Abdominal Wall: burn eschar, repair of gastroschisis or omphalocele, reduction of large hernias, pneumatic anti-shock garments, lap closure under tension, abdominal binders

- Chronic: central obesity, ascites, large abdominal tumors, peritoneal dialysis, pregnancy

Pathophysiology

graph TD

A(Physiologic Insult)

B(Ischemia)

C(Inflammatory Response)

D(Capillary Leak)

E(Tissue Edema)

F("Intra-abdominal Hypertension")

A-->B-->C

A-->C

C-->D

C2(Fluid Resuscitation)-->D

D-->E-->F

An elevated IAP (a) reduces perfusion of surgical and traumatic wounds, liver, bone marrow, etc. and (b) restricts venous return from the legs. This results in poor wound healing, dehiscence, coagulopathy (from decreased blood flow; hemostasis), immunosuppression, and embolic risk (DVT, PE)

- “Second hit” in the two event model of multi-organ failure— deterioration after an initial injury or surgery.

Assessment Findings

- Suspected in critically ill patients. They may complain of lightheadedness, dyspnea, abdominal bloating, or abdominal pain.

- The abdomen is tensely distended, but this is a poor predictor of ACS.

- Progressive oliguria from decreased renal perfusion.

- Hypotension, tachycardia, increased jugular venous pressure and distention, peripheral edema, abdominal tenderness, or acute pulmonary decompensation.

- Imaging is not reliable in ACS, but a CXR can show decreased lung volumes, atelectasis, or elevated hemodiaphragms. A CT can demonstrate infiltration of the retroperitoneum not proportional to other conditions.

Epidemiology

Abdominal Pressure Total Prevalence In MICU In SICU IAP > 12 58.8% 54.4% 65% IAP > 15 28.9% 29.8% 27.5% IAP > 20 with organ failure 8.2% 10.5% 5.0%

Management

- Fluids increase cardiac indices in the early course of management, but will worsen edema over time.

- Vasopressors: perfusion pressure must be increased over 60 mm Hg to ensure continued perfusion.

- Sedation, Paralytics

- Catheterize/Enema

- Colloids

- Hemofiltration

- Paracentesis, if significant free fluid is present

- Decompressive Laparotomy in severe cases

Prognosis (Ivatury, J., 1998)

Of 70 patients with IAP > 25 mm Hg who had surgery were distinguished between having the fascia closed or left open:

- Closed (25 cases): 52% developed IAP > 25 and 39% died

- Open (45 cases): 22% developed IAP > 25 and 10.6% died

Liver Failure

Acute liver failure is a clinical syndrome of severe liver function impairment, which results in encephalopathy, coagulopathy, and jaundice within 6 months of the onset of symptoms. Other classifications of liver failure include:

- Fulminant: the duration between jaundice and encephalopathy takes <2 weeks

- Sub-Fulminant: the duration between jaundice and encephalopathy takes >2 weeks

- Late-onset: encephalopathy begins 8 – 24 weeks after the onset of first symptoms.

Etiology

- Acetaminophen overdose is the most common cause of acute liver failure.

- Prescription medications can cause acute liver failure, such as antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and anticonvulsants.

- Herbal supplements have been linked to acute liver fialure.

- Hepatitis (A, B, E) and other viruses (Epstein-Barr, Cytomegalovirus, HSV)

- Toxins, such as poisonous wild mushrooms

- Autoimmune disease (hepatitis)

- Venous liver disease, e.g., Budd-Chiari syndrome

- Metabolic disease, e.g., Wilson’s disease, acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Infrequent causes.

- Cancer, either of the liver or as metastasis.

Pathogenesis

- Massive destruction of hepatocytes from a directly cytotoxic effect or as an immune response to antigens.

- Impaired hepatocyte regeneration, altered parenchymal perfusion, endotoxemia

Assessment Findings

The clinical features of a patient with acute liver failure typically initially develops non-specific symptoms such as nausea and malaise.

- Jaundice appears and is progressive

- Vomiting is common

- Abdominal pain occurs

- Rapid decrease in liver size without clinical improvement is an ominous sign.

- Ascites

- Tachycardia, hypotension, hyperventilation, and fever are later features.

- Coma and encephalopathy are late features.

Fetor Hepaticus

Fetor hepaticus is a characteristic odor of breath described as sweetish and slightly fecal. This is due to methyl mercaptans excreted through the lungs as the liver is no longer able to continue its normal demethylating process. This often precedes a coma, and is frequent in patients with an extensive portal-collateral circulation.

Skin manifestations appear with acute liver failure from hormonal (the liver metabolizes estrogen) and vascular changes.

- Spider angiomas: over the vascular territory of the superior vena cava, commonly found in the necklace area, the face, forearms, and the dorsum of the hand. It appears as a central arteriole, from which small vessels (like a spider’s legs) radiate outward.

- Palmar erythema: the hands become warm and the palms become bright red in color, with rapid return of color when blanched with pressure.

Hypogonadism

The liver is responsible for hormone metabolism. In liver failure, this mechanism fails, and hormone levels rise. This impairs reproductive functions in both men and women:

- Decreased libido and potency

- Small and soft testes with potentially abnormal seminal fluid

- Loss secondary sexual hair and feminine characteristics (breast, pelvic fat)

- Gynaecomastia (liver failure is the most common cause of this)

Hematology in Liver Failure

- Determine Prothrombin Time (PT)

- CBC: Hgb, WBC, Platelet (may be low in disseminated intravascular coagulation)

- Serum studies: glucose, urea, electrolytes, creatinine, bilirubin, albumin (may decrease as disease progresses; indicator of poor prognosis)

- Liver function tests: transaminases are normally high in liver disease, but these fall as the condition worsens— these carry little prognostic value.

Serology

Virological markers (Serum HBsAg, IgM Anti HBc, IgM anti-HAV, Anti HCV, HCV RNA) can indicate the presence of viruses as the causative factor in acute liver failure

Management

- Volume resuscitation is aggressively carried out. Fluids with glucose are given at an infusion rate of at least 6 to 8 mg/kg/minute, with strict intake-output charting. Fluid shifts and systemic vasodilation occurs in liver failure, making it necessary to restore circulating volume to improve organ perfusion and prevent complications.

- Diet: high carbohydrates, moderate fats, and moderate protein

- Proteins should be vegetable-based, not meat-based. Proteins in general are kept low if encephalopathy occurs. Proteins produce ammonia when digested.

Complications

Acute liver failure can result in death through cerebral edema, infection, bleeding, respiratory and circulatory failure, renal failure, hypoglycemia, and pancreatitis. Complications of liver failure mainly include:

- Hepatic encephalopathy

- Porto-systemic encephalopathy

- Cerebral edema (intracranial hypertension): a common cause of death

- Metabolic, electrolyte, and acid-base disturbances

Hepatic Encephalopathy

If acute liver failure progresses to hepatic encephalopathy, three broad areas of treatment are required:

- Identify the precipitating cause

- Reduce the production and absorption of gut-derived ammonia and other toxins, such as dietary protein (reduce in diet), enteric bacteria (alter with antibiotics/lactulose; stimulate colonic emptying with enemas/lactulose)

- Antibiotics (Neomycin, generally orally; Metronidazole seems as effective) is very effective in decreasing gastrointestinal ammonium formation. This is used in the acute phase for 5 to 7 days. Rifaximin is also effective for non-comatose hepatic encephalopathy

- Lactulose is given by mouth, and is broken down into lactic acid in the cecum. This drops the fecal pH, which reduces ammonia absorption. This also suppresses ammonia-forming organisms (Bacteroides)

- Modify neurotransmitter balance directly: Bromocriptine, Flumazemil (this has limited clinical value)

Coagulopathy

The liver is a producer of clotting factors. In failure, coagulopathy can occur.

- IV Vitamin K to correct reversible coagulopathy.

- Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP) in hemorrhage or severe coagulopathy (PT > 60s)

- Correct thrombocytopenia

- GI Bleeding Prophylaxis with PPIs, Sucralfate (a protectant), and Ranitidine (H₂ antagonist)

Metabolic and Electrolyte Imbalances

- Hyponatremia

- Hypokalemia: decreased dietary intake, chronic illness, secondary hyperaldosteronism, frequent GI losses

- Hypophosphatemia: the regenerating liver uses up phosphate for tissue repair.

- Hypoglycemia: failure of hepatic gluconeogenesis and increased plasma insulin levels from decreased uptake.

- Respiratory Alkalosis: hyperventilation from direct stimulation of the respiratory center by toxic substances.

Hepatorenal Syndrome

The most common cause of renal insufficiency in ALF. This occurs secondary to renal vasoconstriction. There are two types of progression of this syndrome:

- Type 1: rapidly progressive deterioration— creatinine levels double to >2.5 mg/dL or creatinine clearance drops by 50% to <20 mL/min in less than two weeks.

- Type 2: slow progression, taking over two weeks.

The main focus of treatment is to decreased splanchnic circulation with vasoconstrictors (Terlipressin) and alpha agonists (Norepinephrine, Medodrine). These are very effective in reversing functional renal insufficiency.