Reference

Salustiano, R. (2024). The Intrapartal Period. In Dr. RPS Maternal & Newborn Care: A Comprehensive Review Guide and Source Book for Teaching and Learning (2nd ed., pp. 222–261). C&E Publishing, Inc.

The intrapartal period contains a series of physiologic and mechanical processes by which all the products of conception (baby, placenta, and fetal membranes) are expelled from the birth canal. Labor is also called travail, accouchement, parturition, and confinement. The woman in labor is called the parturient. The real cause of labor is unknown, but there are various theories of labor:

- Uterine Myometrial Irritability/Uterine Stretch Theory: considered as the most acceptable theory; when the uterine muscles get stretched with fetal growth and increasing amniotic fluid, it results in irritability and contractions to empty the contents of the uterus.

- Low Progesterone Theory/Progesterone Deprivation Theory: labor is said to start when progesterone (a uterine muscle relaxant) decreases and uterine muscle stimulants increase in late pregnancy.

- Oxytocin Theory: the pressure of the fetal head on the cervix in late pregnancy stimulates the posterior pituitary gland to secrete oxytocin, which causes uterine contractions.

- Estrogenic, Fetal Hormone, and Prostaglandin Theories: all of these have a stimulating effect on the uterine musculature, causing uterine contractility.

- Theory of Aging Placenta: as the placenta matures, more pressure is exerted on the fundal portion, the usual placental site, and the most contractile portion of the uterus. It is believed that the resultant diminished blood supply to the area causes contraction.

Premonitory Signs of Labor

- Lightening: the descent/dipping, dropping of the presenting part to the true pelvis. Engagement is not the same as lightening. The head is said to be “engaged” when the largest diameter of the presenting part passes through the pelvic inlet or the pelvic brim. This occurs earlier in primigravidas, at one to two weeks before labor, and later in multigravidas, at one to two days before labor. There are various signs of lightening:

- Relief of dyspnea

- Relief of abdominal tightness

- Increased frequency of urination, varicosities, and pedal edema because of pressure on the bladder and pelvic girdle

- Shooting pains down the legs because of the pressure on the sciatic nerves

- Increased amount of vaginal discharge

- Braxton Hicks Contractions are another sign, beginning 3 to 4 weeks before labor. They are painless and false labor contractions, appearing intermittently, irregularly, and non-progressively. They do not progress cervical dilatation or effacement, produce abdominal (not lumbosacral) discomfort, and can be relieved by walking and edema. They last anywhere from 30 to 120 seconds, maybe feeling like a wide belt tightening around the front of the abdomen.

- Increased maternal energy/burst of energy because of the hormone epinephrine

- Slight decrease in maternal weight by 2 to 3 lbs, 1 to 2 days before labor. Before labor, there is a drop in the blood level of progesterone, a water-retaining hormone, causing the excretion of retained fluid.

- Show: blood-tinged mucus discharged from the cervix shortly before or during labor.

- Ripening of the Cervix: becomes soft as butter.

- Rupture of the Bag of Waters: an occasional sign. It is an indication for hospitalization.

- Progressive Fetal Descent

- Increased backache and sacroiliac pressure due to fetal pressure.

| Criteria | True Labor | False Labor |

|---|---|---|

| Contractions | Regular, progressive | Irregular, non-progressive |

| Discomfort | Lumbo-sacral radiating to the front; increasing intensity | Abdominal |

| Cervix | Dilated; the most important sign | No dilatation |

| Walking | Intensifies contractions | No effect on contraction |

| Enema | Intensifies contractions | No effect on contraction |

| Show | Present and increasing | Absent |

Physiologic Alterations in Labor

- Dilatation: progressive opening/widening of the cervical os. It is expressed in centimeters, described as “opening”, “widening”, “enlarging”, or “increasing in diameter”. It specifically refers to the cervical external os (a cervical dilatation of 3 cm means the cervical external os is 3-cm open). 10 cm is a fully dilated cervix, the end of the first stage of labor.

- Effacement: thinning and obliteration of the cervical canal. It is expressed in percentage, described as “thinning”, “shortening”, or “narrowing”. A 100% effaced cervix is a fully effaced cervix where the cervical canal has become paper thin or is already absent.

- Physiologic Retraction Ring: the separation of the active, shorter, thicker upper uterine segment an the passive, longer, and thinner lower segment. The Bandl’s Ring is a pathologic retraction ring, formed when the upper uterine segment is as active as the lower segment; seen as an abdominal indentation ring, signifying impending rupture of the uterus if not managed.

Components of the Labor Process (5 Ps)

Power

- Uterine Contractions: the primary power of labor. An involuntary, rhythmical, regular activity of uterine musculature. It occurs intermittently by allowing for a period of uterine relaxation between contractions; uterine and maternal rest and restoration of uteroplacental circulation; sustained fetal oxygenation. This propels the presenting part downward or forward, and aids in progressing dilatation and effacement.

- Contractions increase maternal BP due to increased peripheral arteriole pressure. Measurement of BP should be between contractions to gain accurate results.

- Myometrial contractions constrict blood vessels, decreasing uteroplacental circulation. As such, prolonged uterine contractions can cause fetal hypoxia.

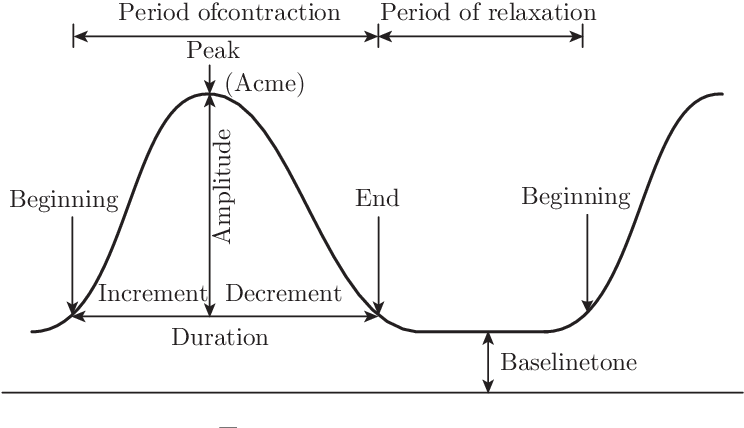

- Contractions can be graphed into three parts, and have relevant durations, intervals, and frequency:

- Increment: increasing or “building up” contraction; the first and longest phase.

- Acme: the apex, height, or peak of the uterine contractions.

- Decrement: the phase of decreasing contraction; “letting up”. The last/end phase.

- Duration: the period from increment to decrement. Measured in seconds.

- Contractions lasting more than 90 seconds can lead to fetal distress, and is called a tetanic contraction.

- Interval: the period from the end to the start of another contraction. It is the uterine resting time, and should be at least 1 minute, not less than 30 to 45 seconds. It is measured in minutes.

- Frequency: the period from the start of one contraction to the start of the next contraction. It is effectively duration plus the interval. Measured in minutes.

Palpation of Contractions

Place the hand lightly on the fundus with the fingers spread; described as mild, moderate and strong by judging the degree of indentability/depressability of the uterine wall during acme. If indentation is not possible, the contraction is strong; difficulty, moderate; and mild if tense but easily indented.

- An intrauterine catheter can be used to directly measure the strength of contractions. At acme, intensity ranges from 30 mm Hg to 55 mm Hg of pressure. The resting tonus average is 10 mm Hg. A major disadvantage of this method involves the requirement of a ruptured bag of water and invasiveness.

- Secondary Powers: maternal bearing down/pushing. Only done on full dilation (10 cm), and a fetal station of +1 (able to stimulate the Ferguson reflex, which is triggered by pressure on the pelvic floor).

- Bearing down should not be done prior to full dilation due to the risk of lacerations.

- Teach the mother to take a deep breath as soon as the next contraction begins, and then, with breath held, exert a downward pressure exactly as though she were straining at the stool. She should not hold her breath for longer than six seconds, during pushing. Involuntary pushing, grunting, groaning, exhaling, or breath-holding for less than seconds is supported. She should push four or more pushes per contraction.

Passenger

Refer to Chapter 08: The Fetus During Labor

Passageway

Divided between the soft passages: cervix, vagina, and perineum (potentially lacerated) and bony passages: the pelvis. Problems of the bony pelvis that can influence the progress of labor include heredity, a contracted pelvis due to avitaminosis D or rickets in childhood, infection, accidents, and cephalo-pelvic disproportion (CPD), the leading cause of primary cesarean section.

Psyche

A pregnant woman’s general behavior and influences on her also affect labor progress. Some factors that make labor meaningful, positive or negative, even:

- Cultural influences integrating maternal attitudes; how a particular society views childbirth

- Expectations and goals for the labor process, whether realistic, achievable, or otherwise

- Feedback from other people participating in the birthing process.

This also includes the pregnant woman’s psychologic response to uterine contractions; fear and anxiety affect labor progress. A woman who is relaxed, aware of, and participating in the birth process usually has a shorter, less intensive labor.

Pain, and anticipation of pain can increase emotional tension and increase pain perception. Even though perceptions of childbirth pain are greatly influenced by a lot of factors, such as psychosocial factors, there is a physiologic basis for discomfort during labor.

- First Stage of Labor: distention and dilatation of the cervix is the primary source of pain in the first stage. Pain from the uterus is referred to as dermatoses supplied by the 12th, 11th, and 10th thoracic nerves, with referred pain to the lower abdominal wall and the areas over the lower lumbar region and upper sacrum. Thus, the characteristic sign of pain in true labor is lumbosacral radiating to the abdomen.

- Hypoxia of the uterine muscles during contraction also cause pain.

- Distension and stretching of the lower uterine segment in combination with isometric contraction of the uterus: if the fetus is large, there is more stretching of the lower uterine segment and more pressure on adjacent structures, causing more pain.

- Pressure on adjacent structures.

- Second Stage of Labor: tissue damage in the pelvis and perineum, ischemia/hypoxia of contracting uterine muscles, distention of the vagina and perineum, and pressure on adjacent structures.

- Distention of the vagina and perineum: the nerve impulses travel via the pudendal nerve plexus and enter the spinal cord through the posterior roots of the second, third, and fourth sacral nerves. As such, the pudendal block technique is employed, relieving pain from perineal distention (but not uterine contractions).

- Pressure on adjacent structures: the larger the passenger, the harder the compressing part (fetal occiput in occipitoposterior positions), and the longer the time of pressure on adjacent structures (prolonged contractions); thus, the more pain and discomfort is experienced by the parturient.

Other factors include:

- Childbirth preparation process (classes): considered a valuable tranquilizer during the birth process; could decrease the need for analgesics in labor.

- Support system: the husband’s (or companion of choice) presence in the labor and delivery unit, the nurse’s supportive and caring environment, and therapeutic communication all contribute to the support a mother receives during labor and delivery.

- Previous experiences

Placenta

Cardinal Movements/Mechanisms of Labor

During labor, the fetal head and body must change positions to accommodate the irregular maternal pelvis. These positional changes are termed the cardinal movements, otherwise called the mechanisms of labor, namely: (mn. DFIREERE)

- Engagement: the mechanism by which the greatest transverse diameter of the fetal head (biparietal diameter) passes through the pelvic inlet; the head is fixed in the pelvis.

- Descent: the first requisite for the birth of the baby: the progression of the fetal head through the pelvis. This may occur earlier in a nulliparous woman, and usually begins with engagement in a multiparous woman. The degree of descent is measured by station. It spans from -5 to +5, with 0 at the level of the ischial spines. Each interval measures 1 cm above or below the ischial spines. There are four forces of descent:

- Amniotic fluid pressure; thus, some obstetricians elect to rupture the bag of water with an amniotone (amniotomy) to enhance labor progress

- Direct pressure of the contracting fundus/uterus upon the breech

- Effects of contractions on the diaphragm and abdominal muscle contraction

- Fetal body extension and straightening

- Flexion: the mechanism that occurs when the head meets resistance from the cervix, pelvic floor, and pelvic walls, causing the head to flex so that the chin is brought into contact with the chest. This results in the smallest anteroposterior diameter of the fetal head (suboccipitobregmatic diameter: 9.5 cm) to present into the maternal pelvis.

- Internal Rotation: this mechanism involves the turning of the fetal head from left to right, aligning it with the long axis of the maternal pelvis and causing the occiput to move anteriorly toward the symphysis pubis.

- In internal rotation, the fetal skull rotates from transverse to anteroposterior at the pelvic outlet, which is associated with descent.

- After internal rotation, the occiput is just under the symphysis pubis.

- Not accomplished until the head is engaged; occurs mainly during the second stage of labor.

- Extension: the delivery of the head in vertex presentation, or when the head leaves the pelvic outlet.

- There is a gradual emergence of the occiput just under the symphysis pubis, followed by the face and then the chin.

Meconium Aspiration

As soon as the head is out, even before the chest is born, the mouth and then the nose are wiped clear of secretions to prevent meconium aspiration. Routine suctioning of the newborn is no longer performed in the immediate care of the newborn.

- Restitution: after the head is extended, the neck is twisted, so the head needs to externally rotate to realign with the long axis of the fetus.

- External Rotation: as a continuation of restitution, the shoulders align with the anteroposterior diameter, causing the fetal head to continue to rotate. The trunk navigates through the pelvic cavity, with the anterior shoulder descending first.

- Expulsion: final birth of the baby. A gentle but firm downward pressure/traction of the head is done to deliver the anterior shoulder. Then, the head is gently raised to deliver the posterior shoulder, and the entire body follows without much difficulty. The head is the biggest part of the baby; after the head passes out, the rest of the body follows with no difficulty.

- When the entire body of the baby emerges from the birth canal, birth is complete. The time of birth is recorded and entered in the birth certificate.

- Apply Unang Yakap or the Essential Newborn Care (ENC) protocol if part of the institutional practice.

Contact the Healthcare Provider or Go to the Hospital

- When contractions are regular and becoming increasingly frequent: their duration is 30 seconds and they occur every 5 minutes.

- When show is present.

- When the bag of water ruptures. The rupture of the bag of water is always an indication for seeking medical help.

| Labor Stage | Primigravida | Multigravida |

|---|---|---|

| First Stage: Phases Latent phase (0-4 cm cervix) Active phase (4-8 cm cervix) Transitional phase (8-10 cm cervix); the most difficult for the mother | 8-10 hours 6 hours 2 hours | 5 hours 4 hours 1 hour |

| Second Stage: most difficult for the fetus | Mean: 50 minutes (1 hour) | 20 minutes (0.5 hour) |

| Third Stage: watchful waiting for signs of placental separation and delivery is the most important nursing action | 5-15 minutes, average 5 minutes | 5-10 minutes |

| Fourth Stage: most dangerous for the mother. When the fundus fails to contract and remains atonic in spite of management, the woman can hemorrhage. Postpartum hemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal mortality. | The period of recovery, stabilization, or homeostasis is usually 1 to 2 hours, at most up to 4 hours. |

Stages of Labor

Dilatation Stage

The Dilatation Stage begins with the onset of the first true labor contraction up to full cervical dilatation (10 cm). Power comes from uterine contractions. This stage is further subdivided into three phases:

| Latent | Active | Transition | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dilatation | 1 cm - 4 cm | 4 cm - 8 cm | 8 cm - 10 cm |

| Effacement | Usually complete in primigravidae | Complete effacement | Complete effacement |

| Frequency | >10 min | 3 min - 5 min | 2 min - 3 min |

| Duration | 30 sec | 45 sec - 60 sec | 60 sec - 90 sec |

| Intensity | Mild | Moderate | Strong |

| Behavior | Cooperative | Anxious | Uncooperative |

| Discomforts | - Backache - Abdominal Cramps | - Hyperventilation - Respiratory Alkalosis | - Backache - Pressure on the bladder and rectum - Leg trembling |

| Interventions | - Positioning, Backrub - Companion of Choice | - Drugs for comfort (4 to 6 cm, avoids fetal distress) - Encourage slow breaths or rebreathing with a paper bag or cupped hands. | - Physical comfort with dry linens and cool clothes - Clean up vomitus - Provide a backrub - Coach on breathing technique: pant-blow pattern - Provide psychologic comfort |

| Every pregnancy and birth is unique, so the best intrapartum care for each woman and her baby is individualized, person-centered, respectful, and evidence-based. In the first stage of labor upon admission to the labor unit, greet the patient, admit and orient them to the physical setting and common procedures, and take their history (GPTPALM, EDC/EDD, last meal, allergies, onset of labor, status of bag of waters, intent to breastfeed). Assess their knowledge about labor and preparedness. Take initial vital signs and FHT. |

- Perform Leopold’s Maneuver. Remember to empty the bladder, flex the knees, and warm hands.

- Do perineal preparation; observe the principles of asepsis.

- Render an enema only if ordered. Removal as a routine procedure reduces infection, labor retardation, and postpartum discomfort.

- Obtain specimens for laboratory: urine (sugar, protein, acetone) and blood (Hgb, Hct, WBC, serology, cross-matching).

Monitor for uterine contractions, the bladder, FHT, perineum (Show), rupture of BOW, presenting part, bulging, cord prolapse, bleeding; ability to manage pain.

- BP, PR, and RR every hour in the latent and active phases, and every 30 minutes in the transition phase (if normal).

- Temperature every 4 hours (if normal), and hourly if above 37.5°C or if membranes rupture (leading complication of prolonged rupture of the bag of water is infection).

- FHR: every 30 minutes in the latent phase, every 15 minutes after (if normal).

Prevent supine hypotensive syndrome. Position the patient in a left lateral recumbent position. Employ physical and psychologic comfort and support; comfort measures such as assisting with positional change, keeping clean and dry, and promoting sleep and adequate rest are observed.

- Distraction is one of the methods used to increase relaxation and cope with the discomfort of labor when contractions are mild to moderate. Examples include “happy thoughts”, conversation, light activities (reading, card play, ambulation), and visualization.

- Massages, particularly effleurage, is a light abdominal stroking, which may be used in the first stage to maintain relaxation of the abdominal muscle; effective for mild to moderate pain.

- Back ache is particularly severe in occipitoposterior positions. Pain may be relieved by counter-sacral pressure and a side-lying position.

Always watch for DANGER SIGNALS

- Hypertonic or hypotonic contractions

- Bleeding (placenta previa, abruptio placenta, uterine rupture)

- Passing of meconium-stained amniotic fluid (fetal distress)

- Severe headache, dizziness, and blurring of vision (PIH)

Delivery/Expulsion Stage

The Delivery/Expulsion Stage lasts from full cervical dilatation to the delivery or expulsion of the baby. This stage features the inclusion of secondary powers (maternal pushing, intraabdominal pressure) in the birthing process.

Pushing in the Crowning Stage

Pushing spontaneously occurs with contractions, but panting should be done during interval and at crowning time. Crowning is the hallmark of the second stage. At this period, pushing is not recommended as the fetus undergoes extension, and alteration with pushing can cause perineal lacerations, and meconium aspiration.

- The strength, duration, and frequency of contractions do not vary from the transition phase.

- The perineum bulges; the mother grunts when pushing. There is an increase in show, leg cramps can occur, and the bag of water ruptures. This stage is the best time for rupture. The first nursing action after rupturing is to check the FHT.

Nursing Implementation

- Continue to offer a psychological support and inform the mother of progress. Use (mn. PRAISE) Praise, Reassurance, Encouragement, Informing the mother of progress, Support System (COC), and Therapeutic Touch.

- Assist/Coach through labor, about when to push or to pant.

- Monitor FHT during intervals (period of rest). If there is a continuous fetal heart electronic monitor, check the FHT during and after a contraction. Be alert for late decelerations.

- Transfer the mother to the delivery room. For primigravidas, with slower progress of labor, they are transferred at 10 cm of dilatation with a certain degree of bulging with contractions. For multigravidas, they are transferred at 8 to 9 cm.

- Positioning: lithotomy with padded, equal stirrups, with no pressure on the popliteal region. The legs are placed on the stirrups simultaneously. Alternatively, Fowler’s, side-lying, or squatting can be used if desired, indicated, or supported by the unit policy.

- Perineal Preparation: cleaning of the perineum to prepare for delivery. A front-to-back motion is used.

Assisting Deliveries

Also refer to the Essential Newborn Care protocol (Unang Yakap) as advocated by the Department of Health.

| Indication | Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Extension of the head | Feel the nape for cord presence | Detection of cord coil. Pass it over the head if present, but double clamp and cut if the coiling is tight. |

| Clear the mouth and nose with shallow suctioning via bulb syringe | Prevention of meconium aspiration. Routine (deep) suctioning is not done without proper indications. | |

| Expulsion | Delay clamping and cutting until pulsations disappear. | Improve initial respiratory efforts and prevent anoxia at the time of birth. |

| Dry and wrap the newborn to keep it warm. | Warmth. Neonatal thermoregulation is not yet fully functional. | |

| Place the wrapped newborn on the maternal abdomen. | The provision of warmth, mother-child closeness or bonding, and aid in uterine contraction from the weight of the baby. | |

| Proper identification | A legal and ethical responsibility if the newborn is to be separated from the mother. |

Placental Stage

The Placental Stage is the period from the delivery of the baby to the delivery of the placenta. The powers involved in the delivery of placental delivery is from strong uterine contractions, and maybe maternal pushing once the placenta has fully detached. There are four primary signs of placental separation:

- Calkin’s sign: the first sign; when the uterus changes shape (from discoid to globular) and consistency (becomes firm).

- Uterine mobility: the uterus rises up into the abdomen. Immediately after placental detachment, the fundus is midway between the symphysis pubis and umbilicus, then rises to the level of the umbilicus.

- Sudden gushing of blood from the open blood vessels once connected to the placenta. It is important to distinguish between the normal sudden gushing of blood, and the abnormal “increasing bleeding”.

- Slight lengthening of the cord: the most definitive sign that the placenta has detached.

The placental delivery can be typed according to which side of the placenta appears first:

- Schultze Mechanism: more common; present in 80% of cases. The shiny, “clean”, bluish side is first delivered. Less external bleeding occurs because blood is usually concealed behind the placenta. The separation for the placenta in this type starts with the middle, then to the edges, which gives it an “inverted umbrella” appearance.

- Matthew Duncan Mechanism: present in the remaining 20% of cases. The rough, “dirty”, reddish side is first delivered. More external bleeding occurs, giving the delivery a “bloody” appearance. The separation for the placenta in this type starts with the side, giving it an “umbrella” appearance.

Postpartal Hemorrhage

The normal amount of blood lost in the entire process of delivery is 250 to 300 mL. Blood loss of more than 500 mL is considered postpartal hemorrhage, the leading cause of maternal mortality.

Nursing Implementation

Observe the principles of the placental delivery stage:

- Watchful Waiting (watch and wait for signs of placental separation)

- Not Increasing Fundal Pressure with a pull at the cord, especially if the uterus is relaxed, as these actions could cause uterine inversion, a leading cause of hemorrhage in the third stage of labor.

- Gradual Delivery of the Placenta

- Inspect the placenta for completeness. The major components of a placenta are cotyledons (15 to 20), cord vessels (two arteries and one vein), and complete membranes. This ensures the reduction of potential placental fragment retention, causing hemorrhaging.

Assess the uterus for contraction or firmness. The terms “soft,” “boggy,” and “non-palpable” mean uterine atony. The initial activity of the nurse is to massage the fundus until it is firm. An ice cap may be applied to further contract the uterus, but never a hot water bag. This promotes vasodilation, increasing bleeding.

Oxytocin is ordered by the physician and administered by the nurse after placental delivery. Commonly used drugs include methergine (Methylergonovine maleate) and ergotrate (Ergonovine maleate/Ergometrine). These increase uterine motor activity by direct stimulation of the uterine musculature. Contraction prevents postpartum bleeding from uterine atony and subinvolution. Evaluate for a firm fundus to determine effectivity. This may cause nausea, vomiting, dizziness, headache, hypertension, tinnitus, and hypersensitivity.

After the birthing process, assess vital signs, presence of lacerations, completeness of the placenta, and bleeding. Lower legs slowly. If allowed by the institution, allow mother time with the infant to promote attachment or bonding; breastfeed right on the delivery table.

Recovery

The Recovery Stage is the period of recovery, stabilization, or homeostasis; usually 1 to 2 hours or at most up to 4 hours. Power still remains from uterine contractions that prevent bleeding from the placental site.

- Vital signs every 15 minutes. Blood loss averages 250 mL during delivery. A normal upper limit is 500 mL. More than this amount is defined as postpartum bleeding.

- Blood pressure changes (lower in both systolic and diastolic, increased pulse pressure, slight to moderate tachycardia) occur from blood loss, lifting of the uterus, and redistribution of blood to the venous beds.

- Palpate the fundus every 15 minutes. Check fundal height and position in relation to the umbilicus, and its consistency. In a normal delivery during the recovery stage, the fundus is firm, midline, and at the level of the umbilicus.

- Ask the mother to void prior to any palpation. This promotes maternal comfort and improves finding accuracy from palpation.

- Displacement of the uterus to the side is often due to a distended bladder. Palpate the lower abdomen for a distended bladder, and if it is, stimulate voiding. Displacement can contribute to uterine atony.

- Assess Lochia. Lochia is bright-red during the fourth stage, and can saturate one to two pads in one hour. A reddish color may be maintained for two weeks, but longer periods indicates either retention of small portions of the placenta or imperfect involution of the placental site, or both.

| Parameter | Rubra | Seroa | Alba |

|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Red | Brownish | White |

| Amount | Moderate | Scanty | Slight |

| Time Present | 1 to 3 days | 4 to 10 days (average and at least 7 days) | 10 to 14 days (at most 21 days) |

- Assess the perineum. Note its general appearance, redness, swelling, bruising, and vaginal and suture line bleeding.

- Administer oxytocin medication as ordered. Check blood pressure before and at intervals after; monitor fundal contraction and lochia after administration.

- Check the episiotomy wound or lacerated wound for bleeding, hematoma, or edema. An ice bag applied to the perineum immediately after delivery (and in the first 24 hours) can reduce edema and swelling.

- Promote sleep and comfort. Keep the mother warm, as chills are common in the fourth stage. This may be due to maternal excitement, a sudden drop in maternal hormones (progesterone is thermogenic), the release of intra-abdominal pressure, and fetal blood in circulation.

- Perform a partial bath and peri-care (front to back), and changing wet linens.

- Assess for afterpains; pains that occur upon uterine contraction. Reassure that these are secondary to uterine contractions. An icecap may be placed on the abdomen overlying the fundus for relief, or analgesics may be given as ordered.

- Provide nourishment. The mother may be thirsty and hungry.

Always Provide Respectful Care

Remember that the care of maternity clients should always be respectful. Respectful intrapartum care maintains women’s dignity, privacy, and confidentiality, ensuring freedom from harm and mistreatment, and enabling informed choice during labor and childbirth. This WHO model of intrapartum care provides a basis for empowering all women to access and demand the type of care that they want and need (WHO, 2020c).

Essential Newborn Care

Also known as Unang Yakap (First Embrace), these are four core principles of immediate care of the newborn.

- Immediate and Thorough Drying

- Early Skin-to-skin Contact

- Properly-timed Cord Clamping

- Non-separation of Newborn from Mother for Early Breastfeeding

- (add.) Eyecare and Immunization Procedures

- (add.) Rooming-in

It is a simply, step-by-step, time-bound and cost-effective newborn care protocol developed by the Philippine Department of Health that adopts international evidence-based standards set by the World Health Organization that can improve neonatal as well as maternal care by directly addressing Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 4: Reduce Child Mortality.

- For preparation, prepare

- Three pairs of surgical gloves, two for the obstetrician and one pair for the pediatrician.

- Two warm blankets/towels

- Bonnet

- Cord care set: clamp, scissors

- Erythromycin ointment for eye care

- Vitamin K and Hepatitis B shots

- Perform handwashing following the prescribed 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 counts for each movement.

- Double gloving: put on two sets of sterile gloves.

First Three Minutes

- Call out the time of birth.

- Towel-dry the body of the baby with the first towel for about 30 seconds. Rubbing with adequate force stimulates breathing. Perform a rapid assessment for breathing as you dry the baby. Remove the wet cloth.

- Initiate skin-to-skin contact by placing the baby prone on the mother’s abdomen or between her breasts. Place the bonnet on the baby’s head and use the second linen to keep the infant warm.

- Perform cord care. The methodology outlined below prevents anemia, and protects preterms from intraventricular hemorrhages.

- Remove the first set of gloves before handling the cord.

- Do not cut the cord immediately. Allow the cord pulsations to stop without milking the cord, which usually takes 1 to 3 minutes.

- Clamp the cord two centimeters from the base, and again five centimeters from the base.

- Cut the cord between the two clamps, one centimeter from the first clamp; three centimeters from the base.

- Inject 10 IU of oxytocin intramuscularly into the mother’s arm to prevent uterine atony.

- While maintaining skin-to-skin contact, check on the mother’s condition and deliver the placenta. Check how heavy the mother’s bleeding is. Examine the perineum, lower vagina, and vulva for tears. Clean the mother and keep her comfortable. The skin-to-skin contact promotes bonding, breastfeeding (and neonatal hypoglycemia) and allows colonization with maternal skin flora.

Thirty to Sixty Minutes

- Check the newborn for readiness to breastfeed. This is determined by the licking, rooting, and tagging movements/reflexes. Encourage the mother to nudge the newborn towards the breast for them to seek out the nipple (crawling reflex). Counsel the mother on the proper positioning and nipple attachment of the baby.

- After initial feeding, perform eyecare procedures and administer vaccines. Then, let the baby remain in the mother’s arms as she recovers from giving birth. This is part of rooming-in, where the baby stays with the mother as she is brought to the room/ward. Encourage exclusive breastfeeding for six months.

- Washing the baby or giving the baby a bath should be done at least six hours after birth.

Prohibitions

- Do not suction unless the mouth/nose is blocked with secretions or other materials.

- Do not ventilate unless the baby is floppy/limp and not breathing.

- Do not place the newborn on a cold or wet surface.

- Do not bathe the newborn earlier than six hours of life.

- Do not separate the newborn from the mother as long as the newborn does not exhibit danger signs of respiratory distress and the mother does not need urgent medical stabilization. If the newborn must be separated from the mother, put him/her on a warm and safe surface close to the mother.

- Do not do footprinting as the stamp pad may be a source of infection; the use of an ankle band is sufficient.

- Do not wipe off vernix caseosa, if present, as it helps prevent heat loss.

- Do not manipulate (e.g., routine suctioning) if the newborn is crying and breathing normally to prevent trauma or infection.

- Do not milk the cord toward the newborn.

- Do not touch the newborn while it is on the maternal abdomen unless there is a medical indication.

- Do not give glucose water, formula, or other prelacteal feedings.

- Do not give bottles or pacifiers.

- Do not throw away the colostrum.

- Do not wash away the eye antimicrobial.

- Do not touch the cord stump unnecessarily.

- Do not apply any substances or medicine to the cord stump.

- Do not bandage the cord stump or abdomen.