References

This page is primarily a summary of the already succinct Self-Study Guide for Ergonomics in Healthcare for Registered Nurses by AnsellCARES, an educational institution. It has been further supplemented with the the following:

- EDiS3: Ergonomic principles, Discomfort perception, and muscular Stretching interventions (2023)— an experimentally tested method for mitigating musculoskeletal discomfort.

- Ergonomic Risk-prone Activities in the Intensive Care and Emergency Room: a paper on the development of a risk-assessment method and its implementation within the intensive care and emergency department.

- Ergonomics in Nursing: primarily for their discussion on the alternative systems in place for safe patient handling in terms of lifting and moving patients.

- No-Lift System at the Royal Melbourne Hospital: the policy used within RMH for their implementation of the No-Lift policy sometimes legally required in some states.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) on their publication on safe patient handling for preventing musculoskeletal disorders in nursing homes, discussion on ergonomics, and discussion on weight-lifting limitations by healthcare workers

Ergonomic risks present significant occupational hazards and are a source of injury, especially in the operating room practice setting. This discussion covers the causes and incidence of ergonomic injuries, characteristics of the operating room, roles of ergonomically designed gloves, and best practice techniques to reduce ergonomic-related injuries.

Causes

The two leading causes of work-related ergonomic injuries among hospital workers are overexertion and bodily reactions (48%) such as lifting, bending, or reaching during patient handling, and slips, trips, and falls (STFs) (25%).

Fatigue is another cause of ergonomic-related injuries and staff accidents in the operating room. In particular, this refers to hand fatigue from tedious, repetitive tasks involved in surgical procedures. This is further exacerbated with the use of thick, rigid, slippery, ill-fitting, or uncomfortable gloves. In surgery, this is primarily related to work schedule, sleep, and the incorporation of comfort into the design of the OR and equipment.

Incidence

In the United States, 253,700 work-related injuries and illnesses were reported for 2011. Among these, nursing personnel were among the highest risk for musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs). A publication from OSHA showed data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics that placed Nursing and Residential Care facilities at highest rates of non-fatal occupational injuries and illnesses, at 2.37% of full-time workers, followed by construction at 1.43% of full-time workers.

According to the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics list of occupations at-risk for sprains, strains, nursing personnel, nurse aides, orderlies, and attendants are listed as first and registered nurses (RNs) are sixth.

In the United States, 25% of nurses and nursing assistants change their shifts or took sick days to recover from an unreported injury, 80% report they frequently work with musculoskeletal pain. Work-related injuries were associated with lifting, pushing, and pulling; fatigue; slips, trips, and falls; and work design and repetitive actions.

Ergonomic Considerations in the Operating Room

The surgical practice setting presents additional, unique challenges in regards to ergonomic-related injuries; the occupational hazards inherent to the perioperative practice setting include, but are not limited to transferring, positioning, and repositioning patients; reaching, lifting, and moving equipment; lifting and holding patient extremities for prepping; standing for long periods of time; and holding retractors for extended periods. This, in conjunction with hazards such as instrument placement and design, forward leaning awkward posture, neck posture, screen positioning, OR bed height, and foot pedal placement contribute to discomfort.

- Standing For Long Periods of Time and Fatigue: discomfort in the legs, knees, feet, and lower back; joint locking, as well as varicose vein development. Maintaining static postures can result in surgical fatigue syndrome, which weakens coordination and also decreases reaction times.

- Instrument Design and Placement: awkwardly-sized surgical instruments and other tools force upper arm movement away from the midline and flexion/ulnar wrist deviation, which can lead to upper body discomfort. Increased instrument weight and distance from hand to tool tip can result in neck and shoulder strain.

- Forward-Leaning Positions: lower back muscular activity is used for positions that lean forward. Prolonged static flexion of the neck and lower back leads to pain in those areas.

- Neck Posture and Screen Positioning: looking down requires neck flexion and also increases cervical spine pressure. In minimally invasive procedures (e.g. laparoscopy), neck posture becomes highly dependent on screen positioning— if the screen is above the line of vision, repeated extension to view the screen is done, causing strain.

- OR Bed Height: beds are often set too high; if adjustable, these are typically fitted to the primary surgeon, despite surgical team members being various heights.

- Foot Pedal Placement: pedals with small surface areas limit the range of motion and also require the use of static posture. If tension is high or the positioning is held for an extended period of time, discomfort may occur.

Hand Fatigue

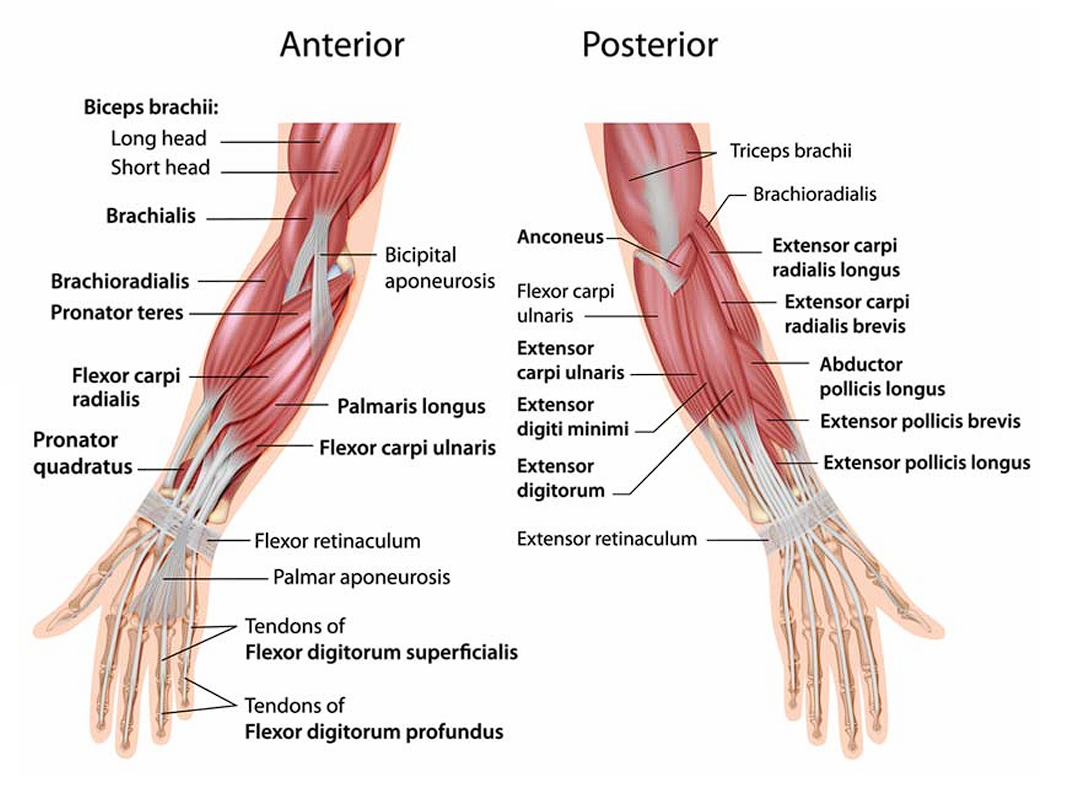

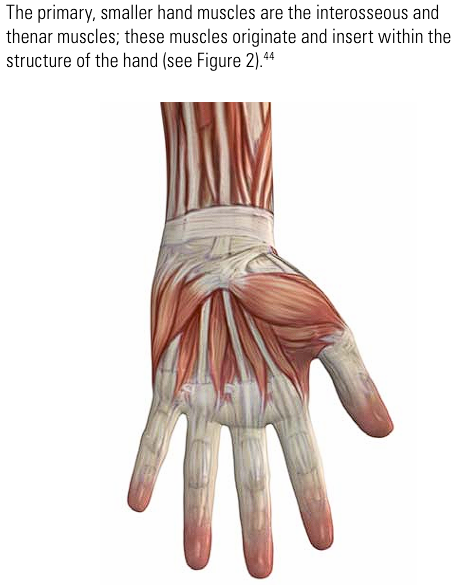

As previously discussed, hand fatigue is common in the OR practice environment. Muscles, nerves, and tendons in the hands, wrists, and arms strain to meet the demanding, tedious, and/or repetitive actions required during surgical procedures, which can be aggravated by gloves that are thick, rigid, slippery, ill-fitting or uncomfortable. (AnsellCARES sells gloves, this might be a conflict of interest but whatever).

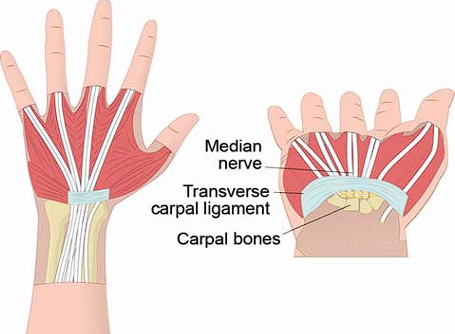

Review of Anatomy

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Gloves that restrict hand movement will require the healthcare worker to exert more muscular effort in order to perform tasks, thereby increasing the risk of strain. Over time, strain caused by repetitive motion or prolonged exertion can lead to muscle fatigue, pain and even injury. In the case of carpal tunnel syndrome, the repetitive stress leads to the swelling and inflammation of tendons, which then creates pressure on the nerves. The affected person becomes symptomatic, with symptoms including burning, tingling, or numbness in the palms and fingers that generally start out gradually. This eventually results in a loss of grip strength, making basic manual tasks difficult. Without treatment, this can cause significant, permanent muscle loss at the base of the thumb. Similar symptoms may also appear in other overuse injuries.

Key Considerations in Glove Use for Hand Fatigue

- The types of gloves worn will affect the amount of hand and finger force associated with a specific task.

- Improperly-sized gloves can either slip too easily, or compress the sensitive muscles with the palm and thumb region, eventually leading to chronic discomfort as well as impairment in mobility.

- As glove thickness increases, tactile sensitivity decreases, which affects instrument/device manipulation.

Ergonomic glove design primarily takes into consideration exertion measurements and comparisons, fit, comfort, performance, tactile sensitivity, donning, and grip. Secondarily, electromyographic measurements were used to quantify muscle effort exerted by individual muscles in the hand during the assigned tasks. These are contrasted with bare-handed use and during the use of comparable products.

Best Preventive Practices

There are many established regulations and best practices outlined by professional nursing associations to prevent ergonomic-related injuries in the O.R.

State No-Lift Laws

In the United States, safe patient handling laws have been published that prohibit the lifting of any patient except in cases of emergency. This is primarily set in place to improve patient safety, but also to reduce carer/healthcare worker injury. In assistance to move is required, staff may use devices to ensure comfortable and safe movement. This may include slide sheets, stand-up lifting machine, lifting machine, turning frames, lateral transfer aids, transfer chairs, gait belts, bedding modifications, geriatric chairs, etc.

Consultation via letter with OSHA (Thomas Galassi) last 2014 yielded a response that, while OSHA does not enforce a minimum amount of lifting required for employees, The American Journal of Nursing (2007, 107(8), 53-58) states that “In general, the revised [NIOSH] equation yields a recommended 35-lb. maximum weight limit for use in patient-handling tasks.”

In the United States, OSHA is a body that enacts laws for employers to ensure workplace safety. They present many salient points in their publication for safe patient handling in nursing homes:

- Patients must realize the ease and comfort of modern mechanical lifts to accept them. The use of mechanical lifts makes care safer for both patients and healthcare workers. It is a misconception to think manual lifting is safer or more comfortable than mechanical lifting.

- There is no such thing as safe manual lifting of a patient. Proper body mechanics, while helpful, is not by itself an effective way reduce the incidence of injuries.

- Patient-handling Injuries are necessary even for healthy workers. Manual lifting can cause micro-injuries to the spine that cumulatively results in debilitating injury. Experts recommend that lifts be limited to 35 pounds or less. Contrarily, good health and strength may put workers at increased risk as they are assigned to manual work such as lifting patients.

- It is faster to use mechanical lifting equipment than manually moving patients (except in some emergent cases). Convenient placement of the equipment is important, and rounding up a team of workers to lift patients is often more time-consuming than to get safe patient handling equipment.

- The use of mechanical lifting is, in fact, cheaper than manual lifting. Injuries will result in the loss of work days. Annually, the healthcare industry loses an estimated $20B from worker compensation, lost productivity, and turnover.

For a successful safe patient handling program, (a) all levels of management must be committed, (b) a safe patient handling committee involving frontline workers must be formed, (c) hazard assessment must be performed, (d) technology and prevention through design is utilized to its best degree, and (e) education and training is provided to each worker, including the use of appropriate patient lifting equipment, review of evidence-based practices, and training for when and how to report injuries.

Professional Guidelines and Recommendations

- American Nurses Association: The ANA supports policies and actions result in the elimination of manual patient handling, in order to provide a safe environment of care for both nurses as well as patients. The ANA’s Handle with Care® Campaign is designed to develop and implement a proactive, multi faceted plan to support the issue of safe patient handling and the prevention of MSDs among nurses in the United States. One component of this campaign is the effectiveness of safe patient handling equipment and devices, which has eliminated manual patient handling in nursing care. This has shown reductions in injuries, lost work days, and worker’s compensation costs.

- Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN): AORN has published and regularly maintain three documents related to reducing work-related injuries (visit AORN Guidelines website where the relevant readings are hosted). They provide guidelines related to perioperative activities that often result in injury. Additionally, they provide the following for an ergonomically healthy perioperative environment:

- Educating staff members on the use of patient handling devices and strategies to prevent musculoskeletal injuries

- Having appropriate assistive patient handling equipment available

- Covering equipment cables across the floor

- Using anti-fatigue mats: mats that provide cushioning and shock absorption, and encourages foot movement that activate leg muscles (by making you less stable) and improve circulation. This effectively reduces fatigue associated with prolonged standing.

- Using lift teams and assistive devices to lift or transfer patients.

- Australian College of Perioperative Nurses (ACORN): The ACORN Standards for Perioperative Nursing in Australia constitutes the specialty knowledge of the perioperative nursing community in Australia and represents the accepted standard for professional practice. Access can be obtained on their website.

Ergonomic Risk Reduction Strategies

- Stranding for Long Periods of Time and Fatigue: rest breaks should be incorporated frequently into the workday. Surgeons and other team members should try to vary posture while operating, when possible. Anti-fatigue mats should be used during prolonged periods of standing to reduce discomfort.

- Instrument Design and Placement: instrument handles should be placed at the elbow height of the surgeon. Instruments and other devices should be selected based upon ergonomic guidelines, such as permits one-handed use; interchangeable shafts; buttons are easily accessible; allows both force and precision grip; can be held comfortably throughout various rotations; and requires low amounts of force to operate.6

- Forward Leaning Postures: Personnel should stretch frequently and take rest breaks. Forward tilting sitting stools can be used, depending on the user; however, these can cause compression on the chest and/or abdomen and lead to discomfort.

- Neck Posture and Screen Positioning: Monitors used in minimally invasive surgical procedures should be set at a visible distance, without causing HCWs to lean forward or squint. The monitor height should be set so that the top of the screen is at eye level. Ideally, monitors are situated on a flexible arm.

- O.R. Bed Height: The OR bed height should be set so that the instruments and equipment being used by the surgeon are positioned at elbow height. This requires height adjustability, but unfortunately does not fi t the work surface to the entire surgical team. Alternatively, the surgeon could stand on a height adjustable platform.

- Foot Pedal Placement: The foot pedal should be placed so that it is aligned in the same direction the surgeon is facing, in order to minimize twisting of the body and/or leg. Foot pedals with a built-in footrest that alleviates the need to repetitively lift and lower the foot from the floor can be considered for use.

Equipment and devices specifically designed to prevent ergonomic-related injuries in the OR include

- Patient Transfer Sheets. friction-reducing, patient transfer and repositioning sheets designed to prevent disabling back injuries to HCWs by reducing physical strain on the back, shoulders, neck and arms.

- Anti-fatigue mats. Anti-fatigue mats are designed to decrease stress and strain placed on muscles and joints due to static positions, e.g., standing during lengthy procedures.

- Ergonomic step stools. Step stools designed with a cushioned top can provide comfort and support during prolonged standing.

- Trip management system. This system consists of a cord cover designed to reduce trips and falls caused by cords and tubings on the OR floor.

- Fluid management systems and absorbent floor pads. To prevent slips and falls in the OR, one of the best measures is to control fluids at their source, i.e., so that they never reach the floor. Proactive measures that can prevent OR floors from becoming wet include absorbent pads placed on the floor around the OR table. Fluid waste management systems include intraoperative floor suction devices, generally used in high-fluid-volume cases (e.g., arthroscopies); and fluid collection systems, i.e., drapes that incorporate fluid collection bags.